By Jeffrey Gettleman and Maria Abi-Habib | The New York Times

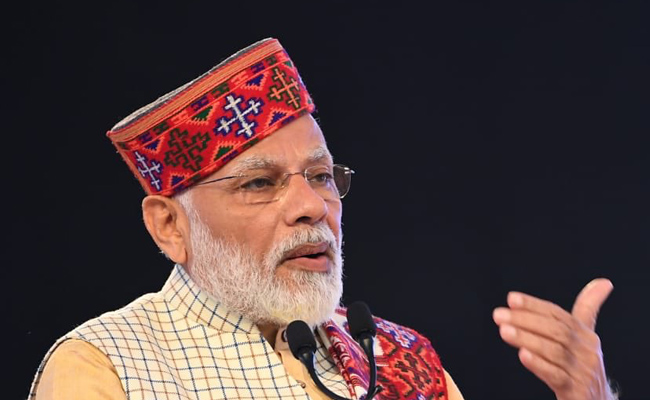

NEW DELHI — Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government has rounded up thousands of Muslims in Kashmir, revoked the area’s autonomy and enforced a citizenship test in northeastern India that left nearly two million people potentially stateless, many of them Muslim.

But it was Mr. Modi’s gamble to pass a sweeping new citizenship law that favors every South Asian faith other than Islam that has set off days of widespread protests.

The law, which easily passed both houses of Parliament last week, is the most overt sign, opponents say, that Mr. Modi intends to turn India into a Hindu-centric state that would leave the country’s 200 million Muslims at a calculated disadvantage.

Indian Muslims, who have watched anxiously as Mr. Modi’s government has pursued a Hindu nationalist program, have finally erupted in anger. Over the past few days, protests have broken in cities across the country.

Mumbai. Chennai. Varanasi. Guwahati. Hyderabad. Bhopal. Patna. Pondicherry. The disturbances keep spreading, and on Monday they tied up several areas of the capital, New Delhi.

Mr. Modi’s government has responded by calling out troops, shutting down the internet and imposing curfews, just as it did when it clamped down on Kashmir. In New Delhi, police officers beat unarmed students with wooden poles, dragging them away and sending scores to the hospital. In Assam, they shot and killed several young men.

India’s Muslims had stayed relatively quiet during the other recent setbacks, keenly aware of the electoral logic that has pushed them to the margins. India is about 80 percent Hindu, and 14 percent Muslim, and Mr. Modi and his party won a crushing election victory in May and handily control the Parliament.

But Indian Muslims are feeling increasingly desperate, and so are progressives, many Indians of other faiths, and those who see a secular government as fundamental to India’s identity and its future.

The world is now weighing in, too. United Nations officials, American representatives, international advocacy groups and religious organizations have issued scathing statements saying that the citizenship law is blatantly discriminatory. Some are even calling for sanctions.

Critics are deeply worried that Mr. Modi is trying to wrench India away from its secular, democratic roots and turn this nation of 1.3 billion people into a religious state, a homeland for Hindus.

“They want a theocratic state,’’ said B.N. Srikrishna, a former judge on India’s Supreme Court. “This is pushing the country to the brink, to the brink of chaos.”

“This is how waves of communal violence start in the country,” he added.

Mr. Modi is no stranger to communal violence. The worst bloodshed that India has seen in recent years exploded on his watch, in 2002, in Gujarat, when he was the top official in the state and clashes between Hindus and Muslims killed more than 1,000 people — most of them Muslims.

Mr. Modi was widely blamed for not doing enough to stop it. Courts have cleared him, but many people believe he was at least partly responsible for the brutality that unfolded.

His grip on power is still firm, even with a weakening economy. The political opposition, including the once-dominant Indian National Congress party, has been disorganized and shaky compared with the juggernaut he and his right-hand man, Amit Shah, the home minister, have built in their Bharatiya Janata Party.

But this contentious citizenship law, which paves a special path for non-Muslim migrants in India to become citizens, has galvanized the opposition. Rival opposition leaders who usually can’t agree on anything are planning protests together. Students from across the country are rallying to each other’s defense. Each episode of harsh police action captured by mobile phone and beamed around cyberspace catalyzes more sympathy, more protests — and more prospects for violence.

On Monday, Mr. Modi called for calm, saying on Twitter that the law “does not affect any citizen of India of any religion” and “the need of the hour is for all of us to work together.’’

This citizenship law was a much touted campaign promise and a special wish of his Hindu base. His supporters see a future India as a place that emphasizes its Hindu heritage as much as possible and eliminates the special legal protections that exist for Muslims and other minorities.

Some analysts are quick to point out that the course Mr. Modi’s party is charting could lead to an India dominated by one faith and one viewpoint, where existential tensions hold back the economy and hamstring politics — as embodied by Pakistan, India’s struggling, Islamic archenemy next door.

“We’re chasing a failed dream,’’ said Yogendra Yadav, a political commentator.

The new citizenship legislation, called the Citizenship Amendment Act, expedites Indian citizenship for migrants from some of India’s neighboring countries if they are Hindu, Christian, Buddhist, Sikh, Parsee or Jain. Only one major religion in South Asia was left off: Islam.

Indian officials have denied any anti-Muslim bias and said the measure was intended purely to help persecuted minorities migrating from India’s predominantly Muslim neighbors — Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh.

The legislation follows hand in hand with a divisive citizenship test conducted this summer in one state in northern India and possibly soon to be expanded nationwide.

All residents of Assam, along the Bangladesh border, had to produce documentary proof that they or their ancestors lived in India since 1971. Around two million of Assam’s population of 33 million — a mix of Hindus and Muslims — failed to pass the test and now risk being rendered stateless. Huge new prisons are being built to house anyone determined to be an illegal immigrant.

A widespread belief is that the Indian government will use both these measures — the citizenship tests and the new citizenship law — to strip away rights from Muslims who have been living in India for generations. The way this will happen, many Muslim Indians fear, is that they will be asked to produce old birth certificates or property deeds necessary to prove citizenship and they will be unable to do so. And while Hindu residents in the same situation will be given a pass, it seems, Muslim residents will not have the same legal protections.

The protests started last week in Assam, led by Hindus and joined by Assamese Muslims and Christians. Many Hindus in Assam don’t like the new law either: They fear it could open the floodgates to poor migrants who will settle in Assam and take their land. And so, despite the legislation’s potential to drive a sectarian wedge across India, in Assam it backfired, unifying protesters across religious lines.

Witnesses said that security forces fired live ammunition into a crowd, killing a 17-year-old Christian student as he walked home. Outraged demonstrators then burned down train stations and attacked the police.

Struggling to maintain control, the central government sent in the army and shut down the internet. The angry crowds only grew.

On Sunday, the protests spread to Delhi. Students of Jamia Millia Islamia University, a predominantly Muslim institution, gathered peacefully, witnesses said. But chaos broke out after a separate group of violent protesters joined the fray and began clashing with the police, witnesses said.

The police response was swift and indiscriminate, according to witnesses, and videos widely circulated on social media showed officers beating students. In one video, a group of female students tries to rescue a young man from the grasp of the police. A squad of officers in riot gear tears him away and knocks him down with heavy blows. Even after the women form a protective circle around him, officers can be seen jabbing the young man with their wooden poles.

Observers said that while police brutality was common in poorer, more rural areas of India, it was extremely unusual to see it explode on such a scale in the capital.

Waqar Azam, a 26-year-old student, was studying in the university library when students burst in and yelled that the police were coming. The students locked the doors. Moments later, tear gas canisters crashed through the windows, filling the library with choking smoke.

“What is happening to Indian Muslims today did not happen overnight,” Mr. Azam said. “If we don’t protest against it now, we will end up living like slaves.”

Mr. Modi’s supporters have dismissed the protesters as being exclusively Muslim, or from a die-hard political opposition group. But in Assam, many protesters said they had voted for the Bharatiya Janata Party and now regretted it.

On Monday morning, some 5,000 protesters, of many faiths, gathered in central Guwahati, Assam’s capital.

One chant echoed across town: “Down with Modi!”

— Reporting was contributed by Suhasini Raj from Guwahati, India, by Vindu Goel from Mumbai and by Hari Kumar, Shalini Venugopal, Sameer Yasir and Karan Deep Singh from New Delhi.

— Jeffrey Gettleman is the South Asia bureau chief, based in New Delhi. He was the winner of a Pulitzer Prize in 2012 for international reporting.

— Maria Abi-Habib is a South Asia correspondent, based in Delhi. Before joining The Times in 2017, she was a roving Middle East correspondent for The Wall Street Journal.

A version of this article appears in print on Dec. 17, 2019, Section A, Page 1 of the New York edition with the headline: India Erupts in Protests as Modi Presses Vision for Hindu Nation.