India’s endgame in Kashmir is the consummation of settler-colonial occupation; Kashmiris’ goal is to uproot it

Written by: Tariq Ahmed

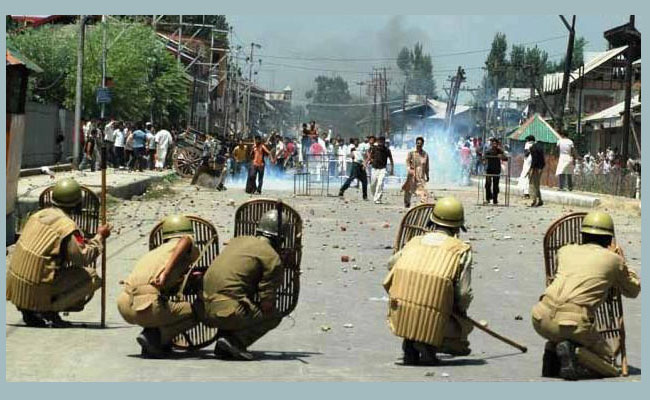

Kashmir and India have been in a state of political turmoil for a long time. The theater of the conflict has been and is Kashmir. The stakes are high for both. For the Indians, the endgame is consummating the settler-colonial occupation. For the Kashmiris, the goal is to resist and uproot it. It is a resistance of unfortunate people pushed to the wall by a hegemonic occupier.

At stake are the lives of and the nationhood for Kashmiris. A colonial power has violently usurped their land against their wishes. The colonial power has tried every means conceivable in the ‘counterinsurgency’ to contain and quell resistance against its rule., The caravan of coloniality began around the Partition and is now at its culminating point where the next step is memorised and erasure.

In contrast to appearances, there is no letup in the state-sponsored repression, nor have Kashmiris given up; their resistance is in suspended animation. How else could one explain the repetition and regurgitating of the same policy mistakes India committed in the past in this century?

A case in point: India’s continuing need for social, political, and militaristic machinations in Kashmir since its occupation in 1947 has not diminished despite India’s decades of political maneuvering and military repression or even after pouring billions in developmental aid. Neither has India’s awe-inspiring rise to the status of an economic superpower made a dent in the resistance narrative. They have been able to subdue the resistance narrative yet have been unable to erase it.

In this sense, then, not much has changed in Kashmir and its fraught and testy relationship with India since those days when the settler-colonial project was in its embryonic stage. Now, as then, the Machiavellian social and political engineering has failed to cut it with the Kashmiris. The old game plans continue even today under new actors; only the actors have changed, but the script remains the same.

This matter is a theme of a recent publication, “Colonizing Kashmir: State-building Under Indian Occupation,” by Hafsa Kanjawal. The book is a microscopic insider-outsider account and a reflection of India’s wheeling and dealing to keep its control of Kashmir. The book investigates Kashmir’s formative years of settler-colonial occupation around the Partition. This seminal and detailed work, based on meticulous, if grueling, years of research in Kashmir, challenges many myths about India’s settler-colonial enterprise unabashedly purveyed by the Indian politicians, unsuspectingly accepted by an ordinary Indian citizen, dishonestly unchallenged by the Indian or even international academe, and problematically born by the international community without scrutiny.

The book is a must-read for anyone who cares to know how India’s decades of colonial-settler machinations in Kashmir have led to the intractability of the Kashmir dispute and how some Kashmiri collaborators, the so-called integrationists, willfully contributed to and actualized the process of coloniality for their own personal glory and benefit.

Dr. Kanjwal’s work is a piece of art as much as an expository treatise on the inside story of Kashmir’s potential erasure. The book artfully demonstrates how Nehru and his accomplices in Srinagar (Bakhshi et al.) pinned their hopes on the now-defunct thesis that Kashmiris’ nationalist sentiment was not unwavering and could be modulated through social, educational, political, cultural, economic, and militaristic means. Together, they often invoked state of exception, crises, and emergency, and portrayed Kashmiris as biddable, and Pakistan as an opportunist enemy. This concoction of self-imagined factors then justified and led to an overwhelming response through both ‘politics of life’ as much as through a reign of state-sponsored terror.

Meanwhile, the Indian nationalists projected Kashmir as an exotic land whose integration with the Indian Union was essential or vital to India’s very being, a place of ‘national affect’ and interest whose separation from India could unravel India and impede its progress. Therefore, they did everything in their power to eliminate the Kashmiri nationalist sentiment and subordinate it to that of Indian nationalism. They attempted to de-emphasize the affective causes of the freedom sentiment and highlight the instrumentality of interference of an external power trying to prevent a land grab– the irredentist neighbor, Pakistan.

The nationalists retaliated against Pakistan’s supposed interference by fetishizing and licensing repression against the latter’s so-called ‘Islamist’ loyalists in Kashmir. This tactic simultaneously appeased the unsuspecting Indian citizens while calming any international voices who were less interested in interrogating the dark underbelly of India’s secular-democratic stance.

By introducing bio-power politics in tandem with the necropolitical system of control, India forced not only its colonization of Kashmir’s territorial space but also the colonization of the biological spaces of its citizens — their lives. The state’s overwhelming militarized intelligence apparatus sought a complete submission of those whom it could intimidate, humiliate, or otherwise manipulate and the death of those it could not. They instrumentalized the politics of life, surveillance, and death to bring the citizens’ revolt against its rule under control and legitimize its sovereignty over Kashmir.

Simultaneously, in a carefully crafted strategy directed at denying them agency India deployed cinematic soft power through Bollywood’s fantasy-filled pleasure machine, seeking to obliterate Kashmir’s identity and its mixed cultural ethos and integrate it into the Indian (exclusively Hindu) union. By using Kashmir as an idyllic set for the Bollywood flicks, and by insinuating politically motivated cinematic dialogs they attempted to arouse the lust of an Indian tourist for its exotic land to be desired and eventually claimed and bolstered as part of the Indian nation. The objectives were to manipulate or erase Kashmiri identity and memory and subsume it to an Indian identity and memory.

Overtly, they successfully projected India’s secular facade while covertly, for the domestic audiences, foregrounding Kashmir’s Hindu religious past and downplaying or outright erasing its Muslim heritage and influence. Kanjawal goes on to demonstrate that far from being a secular-democracy, “colonialism and domination were at the root of Indian state-formation.” These strategic measures were intended to justify, rationalize, and routinize the Hinduvized settler-colonial occupation in Kashmir.

They had hoped that the psychological distance between India and Kashmir could be bridged through calibrated doses of tyranny and through some perfunctory salutary means. Apparently, the calculus was that if Kashmiris were not willing to change their hearts in favor of India, they could be receptive or enticed to change their minds against Pakistan or independence.

Thus, Kashmir became a theater of settler-colonial tyranny as well as a case study in ‘developmentalism’ (the cynical ‘politics of life’) that sought to distract the restive population from its political aspiration and focus more on their daily grind of life and living. The refrain was, as is the case in all colonial occupations, “we must develop them, with or without their consent’; a civilizing and redeeming intervention by the ‘well-meaning, cultured and progressive’ Indian for the good of a ‘gullible, primitive and timid’ Kashmiri.

To entrench its stranglehold, India– through devious economic strategies, sinister educational and cultural policies, cunning deployment of cinematic soft power, and brutal silencing of dissent through both hard and ‘soft’ repression — attempted to articulate subjectivities and configure and re-configure political proclivities and aspirations in Kashmir. The sole aim was to legitimize and sustain Kashmir’s continued colonial occupation as a necessity that Kashmiris could not survive without.

When the ‘development and progress’ mantra lost its traction, they enhanced militarized silencing of the dissent. This tyrannical subjugation presented Kashmiris the binary of complete submission or the inglorious life of the ‘living dead.’ In this survival struggle, Kashmiris made a rational choice in choosing to live. This inevitably led to the uneasy co-existence of the tyranny of breathing under a repressive and manipulative regime and the realities of daily living.

Kanjawal notes, “Strategies such as the politics of life build, maintain and sustain colonial occupations. They enable political subjectivities that are paradoxical in their demands and aspirations, forcing individuals to reconcile their desire for political freedom with their desire to lead ‘normal’ economically stable lives.”

The Indian governments of the past and present have succeeded in manipulating and suppressing dissent and immobilizing the street protests. The nationalists have misinterpreted and conflated this as consent to its rule. The inconvenient truth is that instead of following an inverted U-trajectory — a one-off volcanic eruption, the resistance struggle has followed a W-trajectory, going up and down and up again.

India will soon discover that the political resistance against settler-colonial occupation cannot be effectively eliminated by demobilizing street protests. As has been the case in other settler-colonial occupations, India has provided no breathing space for the expression of political dissent to render violent resistance superfluous, and in doing so, created the seeds of a future confrontation.

The book’s premise applies to current and future times as much as it lays bare the past.

Tariq Ahmed is a freelance writer.