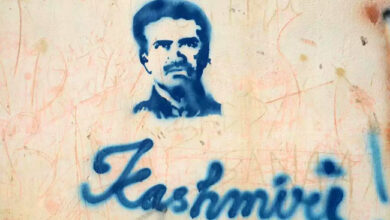

Kashmiri journalists describe new government tactics to control the narrative

By Aliya Iftikhar/CPJ Senior Asia Researcher on August 4, 2020 2:02 PM EDT

In April, after Srinagar-based senior journalist Peerzada Ashiq published an article about the families of two militants who wanted to exhume their bodies to perform funeral rites, police in Kashmir launched an investigation and accused him of publishing “fake news.” Ashiq told CPJ that he had sought official comment on multiple channels, but never received a response. After the article was published, he was summoned for questioning at two separate police stations for several hours.

“I’ve reported on funerals in the past, I’ve visited families affected by the violence from both sides, militant violence or violence perpetrated by the army, but I’ve never seen this kind of retribution from the state for reporting what is happening on the ground,” Ashiq, a correspondent for the national daily The Hindu, told CPJ on a phone call.

One year after the Indian government unilaterally revoked Article 370, which granted Jammu and Kashmir limited governing autonomy, and split it into two union territories–bringing it directly under federal control–journalists in Kashmir say government attempts to control the press are reaching new heights. The space for press freedom has deteriorated drastically, with a rise in harassment and intimidation of journalists, ongoing communication restrictions, increased state surveillance, and a proposed new media policy that seems like a “nail in the coffin” for the free press in Kashmir, Raqib Hameed Naik, a freelance journalist based in Jammu, told CPJ via messaging app.

The government wants to control the narrative around Kashmir and ensure that the official statement is the main story, Ashiq said. He described to CPJ how in the year since August 5, 2019, reporters who tell the truth of Kashmir have to be ready to pay a price. He told CPJ that the case against him remains open.

“The whole idea of having an open [investigation] is that whenever [police] want they can summon me to the police station as part of the investigation,” Ashiq said. “So now it’ll hang like a sword on my neck. It will be used as leverage against me and my reporting by the police whenever I try to do any inconvenient reporting.”

In the same week in April, police also launched investigations into journalists Masrat Zahra and Gowhar Geelani under a draconian anti-terror law. After the police investigations, journalists across Kashmir are feeling an extreme sense of fear, Naik told CPJ. He said before he writes a piece that authorities might consider against their interests, he carefully considers the repercussions he might face.

Ashiq told CPJ that there has been a marked shift over the past year in reporting in Kashmir, with coverage of militants and return of bodies almost disappearing as news spread about his police investigation. But Ashiq believes his critical reporting on COVID-19 also drew the government’s ire. The ultimate goal is to control what journalists are covering, he said.

“They’re choking spaces to question or to point out the administration’s mistakes, if they have made any,” Ashiq said. “As a journalist, this is your job, but what they’re trying to do is turn a journalist into an official mouthpiece.”

Dilbag Singh, director general of police in Jammu and Kashmir, did not respond to CPJ’s requests for comment via phone call and WhatsApp message.

Journalists in Jammu and Kashmir have always faced pressure, intimidation, and violence, but after August 5, 2019, the way the government has tried to control the media has become more sophisticated, Raashid Maqbool, a freelance journalist and a media researcher at the University of Kashmir, told CPJ on the phone. Journalists are being stifled and suffocated, he said. CPJ has documented how detentions, legal cases, ongoing restrictions on movement and communications, direct and indirect intimidation, and dwindling advertisement revenues have placed unprecedented pressure on the Kashmiri media.

As journalists tried to work through a near-total communications blackout over the past year, with only a handful of computers to use at the media facilitation center, many local newspapers were only able to carry official government statements, Maqbool said. Press releases that used to be carried on the inner folds of a newspaper now appeared on the front pages, he said.

“The policy was not to shut down the papers, but to prevent anything from being written,” Maqbool said. The government used the example of newspapers continuing to print as justification that things in Kashmir were “normal,” he said.

Even during times of insurgency, journalists didn’t face the level of pressure they are facing from the state today, Haroon Rashid Shah, editor of the Urdu daily Nida-i-Mashriq, told CPJ on the phone.

“I’ll find a way to write, but I’m cautious,” he said. “I’m certainly not free to write what I want.”

Now, journalists fear the administration is attempting to codify that control. In June, the Jammu and Kashmir administration proposed a new media policy—which CPJ has reviewed—aimed at “creating a sustained narrative on the functioning of the government in media” and to “thwart misinformation, fake news, and develop a mechanism that will raise alarm against any attempt to use media to vitiate public peace, sovereignty and integrity of the country.”The policy was proposed without consultation from stakeholders, Moazum Mohammad, vice-president of the Kashmir Press Club, told CPJ on the phone.

The policy includes provisions that allow the government to conduct background checks into the “antecedents” of a journalist or outlet before approval of accreditation and government advertisements, Vrinda Grover, a lawyer and human rights activist based in Delhi, told CPJ via messaging app. The policy also gives the Department of Information and Public Relations wide power to censor all content against subjective and vague benchmarks on reporting that is deemed to be “unethical” or “anti-national” on the premise of fighting “fake news,” she said.

Grover said the measures “leave the door wide open for pre-publication censorship and the sidelining of publications and portals that ask inconvenient questions or don’t toe the government’s line.”

Maqbool said that journalists in Kashmir are left wondering: who gets to decide what “fake news” is? Who gets to decide what quality journalism is? Given the trust deficit with the government, it’s very easy to speculate how these policies could be used against journalists, he said.

“They’re not just worried about human rights abuses, they’re worried about the thinking class in Kashmir getting an expression through newspapers,” Ashiq said.

And while the policy hasn’t been enacted yet, Qurutalain Rehbar, a freelance journalist based in south Kashmir, told CPJ that it was already impacting journalists in Jammu and Kashmir. As a looming threat that the government could enact at any time, she said it’s having a psychological effect on journalists, who are already thinking about the how provisions laid out in the policy could be used against them.

In a recent interview with the Indian Express, Jammu and Kashmir’s Lieutenant Governor Girish Chandra Murmusaid the administration would review the proposal for the media policy. Rohit Kansal, the Jammu and Kashmir administration spokesperson, did not respond to CPJ’s request for comment via phone and WhatsApp message.

But the government has been testing the waters for this new media policy since August 5, 2019, with the summoning of journalists and branding of news as “fake” or “anti-national,” Ashiq said. And in a conflict zone like Kashmir, any reports from the region could be viewed as provoking various sections of society, he said.

“If the state succeeds in implementing this media policy, which has the intentions to choke the spaces further, there will be a point where journalism will be reduced to being an official mouthpiece,” Ashiq said. “Then only official statements will make the news, and nothing else.”